|

| |

| ||

| You are in: Museum of History >> Hall of USA >> US Vice Presidents >> Calvin Coolidge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

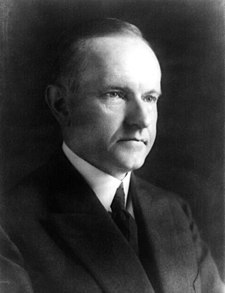

John Calvin Coolidge, Jr. (July 4, 1872 – January 5, 1933) was the 30th President of the United States (1923–1929). A Republican lawyer from Vermont, Coolidge worked his way up the ladder of Massachusetts state politics, eventually becoming governor of that state. His actions during the Boston Police Strike of 1919 thrust him into the national spotlight. Soon after, he was elected as the 29th Vice President in 1920 and succeeded to the Presidency upon the death of Warren G. Harding. Elected in his own right in 1924, he gained a reputation as a small-government conservative. Coolidge restored public confidence in the White House after the scandals of his predecessor's administration, and left office with considerable popularity.[1] As his biographer later put it, "he embodied the spirit and hopes of the middle class, could interpret their longings and express their opinions. That he did represent the genius of the average is the most convincing proof of his strength."[2] Many later criticized Coolidge as part of a general criticism of laissez-faire government.[3] His reputation underwent a renaissance during the Ronald Reagan Administration,[4] but the ultimate assessment of his presidency is still divided between those who approve of his reduction of the size of government and those who believe the federal government should be more involved in regulating the economy.[5]

Family and early life

Birth and family historyJohn Calvin Coolidge, Jr. was born in Plymouth, Windsor County, Vermont, on July 4, 1872, the only U.S. President to be born on the fourth of July. He was the elder of two children of John Calvin Coolidge (1845 – 1926) and Victoria Josephine Moor (1846 – 1885). He had a sister, Abigail Grace Coolidge (1875 – 1890). The Coolidge family had deep roots in New England. His earliest American ancestor, John Coolidge, emigrated from Cambridge, England, around 1630 and settled in Watertown, Massachusetts.[6] Coolidge's great-great-grandfather, also named John Coolidge, was an American army officer in the American Revolution and was one of the first selectmen of the town of Plymouth Notch.[7] Most of Coolidge's ancestors were farmers. The more well-known Coolidges, such as architect Charles Allerton Coolidge and diplomat Archibald Cary Coolidge, were descended from other branches of the family that had stayed in Massachusetts.[6] Coolidge's grandmother Sarah Almeda Brewer had two famous first cousins: Arthur Brown, a United States Senator, and Olympia Brown, a women's suffragist. Coolidge's grandfather Calvin Coolidge held some local government offices in Plymouth and was best remembered as a man with "a fondness for practical jokes".[8] Sarah Brewer was also of New England. It is through this ancestor that Coolidge claimed to be descended in part from American Indians.[9] Coolidge's father was a farmer, but spent some time as a schoolteacher and justice of the peace.[10] His mother Victoria (Moor) Coolidge was the daughter of another Plymouth Notch farmer.[11] Coolidge's mother was chronically ill, possibly suffering from tuberculosis, and died young in 1885, but Coolidge's father lived to see him become President.[12]

Early career and marriage

Western Massachusetts lawyerCoolidge attended Amherst College where he was a member of the fraternity of Phi Gamma Delta (FIJI). After graduating from Amherst College, at his father's urging Coolidge moved to Northampton, Massachusetts to take up the practice of law. Avoiding the costly alternative of attending a law school, Coolidge followed the more common practice at the time of apprenticing with a local firm, Hammond & Field and reading law with them. John C. Hammond and Henry P. Field, both Amherst graduates, introduced Coolidge to the law practice in the county seat of Hampshire County. In 1897, Coolidge was admitted to the bar. With his savings and a small inheritance from his grandfather, Coolidge was able to open his own law office in Northampton in 1898. He practiced transactional law, believing that he served his clients best by staying out of court. As his reputation as a hard-working and diligent attorney grew, local banks and other businesses began to retain his services.[13]

Marriage and familyIn 1905 Coolidge met and married a fellow Vermonter, Grace Anna Goodhue, a local schoolteacher working at the Clarke School for the Deaf. While Grace was watering flowers outside the school one day in 1903, she happened to look up at the open window of Robert N. Weir's boardinghouse and caught a glimpse of Calvin Coolidge shaving in front of a mirror with nothing on but long underwear and a hat.[14] After a more formal introduction sometime later, the two were quickly attracted to each other.[14] They were opposites in personality: she was talkative and fun-loving, while Coolidge was quiet and serious.[15] Not long after their marriage, Coolidge handed her a bag with fifty-two pairs of socks in it, all of them full of holes. Grace's reply was "Did you marry me to darn your socks?" Without cracking a smile and with his usual seriousness, Calvin answered, "No, but I find it mighty handy."[16] They had two sons; John Coolidge, born in 1906, and Calvin Coolidge, Jr., born in 1908.[17] The marriage was, by most accounts, a happy one.[18] As Coolidge wrote in his Autobiography, "We thought we were made for each other. For almost a quarter of a century she has borne with my infirmities, and I have rejoiced in her graces."[19]

Local political office

City officesThe Republican Party was dominant in New England in Coolidge's time, and he followed Hammond's and Field's example by becoming active in local politics.[20] Coolidge campaigned locally for Republican presidential candidate William McKinley in 1896, and the next year he was selected to be a member of the Republican City Committee.[21] In 1898, he won election to the City Council of Northampton, placing second in a ward where the top three candidates were elected.[21] The position offered no salary, but gave Coolidge experience in the political world.[22] In 1899, he declined renomination, running instead for City Solicitor, a position elected by the City Council. He was elected for a one-year term in 1900, and reelected in 1901.[23] This position gave Coolidge more experience as a lawyer, and paid a salary of $600.[23] In 1902, the city council selected a Democrat for city solicitor, and Coolidge returned to an exclusively private practice.[24] Soon thereafter, however, the clerk of courts for the county died, and Coolidge was chosen to replace him. The position paid well, but barred him from practicing law, so he only remained at the job for one year.[24] The next year, 1904, Coolidge met with his only defeat before the voters, losing an election to the Northampton school board. When told that some of his neighbors voted against him because he had no children in the schools he would govern, Coolidge replied "Might give me time!"[24]

State legislator and mayorIn 1906 the local Republican committee nominated Coolidge for election to the state House of Representatives. He won a close victory over the incumbent Democrat, and reported to Boston for the 1907 session of the Massachusetts General Court.[25] In his freshman term, Coolidge served on minor committees and, although he usually voted with the party, was known as a Progressive Republican, voting in favor of such measures as women's suffrage and the direct election of Senators.[26] Throughout his time in Boston, Coolidge found himself allied primarily with the western Winthrop Murray Crane faction of the state Republican Party, as against the Henry Cabot Lodge-dominated eastern faction.[27] In 1907, he was elected to a second term. In the 1908 session, Coolidge was more outspoken, but was still not one of the leaders in the legislature.[28] Instead of vying for another term in the state house, Coolidge returned home to his growing family and ran for mayor of Northampton when the incumbent Democrat retired. He was well-liked in the town, and defeated his challenger by a vote of 1,597 to 1,409.[29] During his first term (1910 to 1911), he increased teachers' salaries and retired some of the city's debt while still managing to effect a slight tax decrease.[30] He was renominated in 1911, and defeated the same opponent by a slightly larger margin.[31] In 1911, the State Senator for the Hampshire County area retired and encouraged Coolidge to run for his seat for the 1912 session. He defeated his Democratic opponent by a large margin.[32] At the start of that term, Coolidge was selected to be chairman of a committee to arbitrate the "Bread and Roses" strike by the workers of the American Woolen Company in Lawrence, Massachusetts.[33] After two tense months, the company agreed to the workers' demands in a settlement the committee proposed.[34] The other major issue for Republicans that year was the party split between the progressive wing, which favored Theodore Roosevelt, and the conservative wing, which favored William Howard Taft. Although he favored some progressive measures, Coolidge refused to bolt the party.[35] When the new Progressive Party declined to run a candidate in his state senate district, Coolidge won reelection against his Democratic opponent by an increased margin.[35] The 1913 session was less eventful, and Coolidge's time was mostly spent on the railroad committee, of which he was the chairman.[36] Coolidge intended to retire after the 1913 session, as two terms were the norm, but when the President of the State Senate, Levi H. Greenwood, considered running for Lieutenant Governor, Coolidge decided to run again for the Senate in the hopes of being elected as its presiding officer.[37] Although Greenwood later decided to run for reelection to the Senate, he was defeated and Coolidge was elected, with Crane's help, as the President of a closely divided Senate.[38] After his election in January 1914, Coolidge delivered a speech entitled Have Faith in Massachusetts, which was later republished as a book.[39] His speech, later much-quoted, summarized Coolidge's philosophy of government.

Coolidge's speech was well-received and he attracted some admirers on its account.[41] Towards the end of the term, many of them were proposing his name for nomination to lieutenant governor. After winning reelection to the Senate by an increased margin in the 1914 elections, Coolidge was reelected unanimously to be President of the Senate.[42] As the 1915 session drew to a close, Coolidge's supporters, led by fellow Amherst alumnus Frank Stearns, encouraged him once again to run for lieutenant governor. This time, he accepted their advice.[43]

Lieutenant GovernorCoolidge entered the primary election for lieutenant governor and was nominated to run alongside gubernatorial candidate Samuel W. McCall. Coolidge was the leading vote-getter in the Republican primary, and balanced the Republican ticket by adding a western presence to McCall's eastern base of support.[44] McCall and Coolidge won the 1915 election, with Coolidge defeating his opponent by more than 50,000 votes.[45] Coolidge's duties as lieutenant governor were few; in Massachusetts, the lieutenant governor does not preside over the state Senate, although Coolidge did become an ex officio member of the governor's cabinet.[46] As a full-time elected official, Coolidge no longer practiced law after 1916, though his family continued to live in Northampton.[47] McCall and Coolidge were both reelected in 1916 and again in 1917 (both offices were one-year terms in those days). When McCall decided that he would not stand for a fourth term, Coolidge announced his own intention to run for governor.[48]

Governor of Massachusetts

1918 electionCoolidge was unopposed for the Republican nomination for Governor of Massachusetts in 1918. He and his running mate, Channing Cox, a Boston lawyer and Speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, ran on the previous administration's record: fiscal conservatism, a vague opposition to Prohibition, support for women's suffrage, and support for American involvement in the First World War.[49] The issue of the war proved divisive, especially among Irish- and German-Americans.[50] Coolidge was elected by a margin of 16,773 votes over his opponent, Richard H. Long, in the smallest margin of victory of any of his state-wide campaigns.[51]

Boston Police StrikeIn 1919 in response to rumors that policemen of the Boston Police Department planned to form a trade union, Police Commissioner Edwin U. Curtis issued a statement saying that such a move would not be countenanced. In August of that year, the American Federation of Labor issued a charter to the Boston Police Union.[52] Curtis said the union's leaders were insubordinate and planned to relieve them of duty, but said that he would suspend the sentence if the union was dissolved by September 4.[53] The mayor of Boston, Andrew Peters, convinced Curtis to delay his action for a few days, but Curtis ultimately suspended the union leaders after a brief delay, on September 8.[54]

The following day about three-quarters of the policemen in Boston went on strike.[56] Coolidge had observed the situation throughout the conflict, but had not yet intervened. That night and the next, there was sporadic violence and rioting in the lawless city.[57] Peters, concerned about sympathy strikes, had called up some units of the Massachusetts National Guard stationed in the Boston area and relieved Curtis of duty.[58] Coolidge, furious that the mayor had called out state guard units, finally acted.[59] He called up more units of the National Guard, restored Curtis to office, and took personal control of the police force.[60] Curtis proclaimed that none of the strikers would be allowed back to their former jobs, and Coolidge issued calls for a new police force to be recruited.[61] That night Coolidge received a telegram from AFL leader Samuel Gompers. "Whatever disorder has occurred", Gompers wrote, "is due to Curtis's order in which the right of the policemen has been denied …"[62] Coolidge publicly answered Gompers's telegram with the response that would launch him into the national consciousness (quoted, above left).[62] Newspapers across the nation picked up on Coolidge's statement and he became the newest hero to defenders of American capitalism. In the midst of the First Red Scare, many Americans were terrified of the spread of communist revolution, like those that had taken place in Russia, Hungary, and Germany. While Coolidge had lost some friends among organized labor, conservatives across the nation had seen a rising star.

1919 electionCoolidge and Cox were renominated for their respective offices in 1919. By this time Coolidge's supporters (especially Stearns) had publicized his actions in the Police Strike around the state and the nation and some of Coolidge's speeches were reissued as a book.[39] He was faced with the same opponent as in 1918, Richard Long, but this time Coolidge defeated him by 125,101 votes, more than seven times his margin of victory from a year earlier.[63] His actions in the police strike, combined with the massive electoral victory, led to suggestions that Coolidge should run for President in 1920.[64]

Legislation and vetoes as governor

Governor Coolidge, laying the cornerstone at Suffolk Law School in Boston in August of 1920. By the time Coolidge was inaugurated on January 2, 1919, the First World War had ended, and Coolidge pushed the legislature to give a $100 bonus to Massachusetts veterans. He also signed a bill reducing the work week for women and children from fifty-four hours to forty-eight, saying "we must humanize the industry, or the system will break down."[65] He signed into law a budget that kept the tax rates the same, while trimming four million dollars from expenditures, thus allowing the state to retire some of its debt.[66] Coolidge also wielded the veto pen as governor. His most publicized veto was of a bill that would have increased legislators' pay by 50%.[67] In May 1920, he vetoed a bill that would have allowed the sale of beer or wine of 2.75% alcohol or less, in contravention of the Eighteenth Amendment. Although Coolidge himself was opposed to Prohibition, he felt constrained to veto the bill. "Opinions and instructions do not outmatch the Constitution," he said in his veto message, "Against it, they are void."[68]

Vice Presidency

1920 electionAt the 1920 Republican Convention most of the delegates were selected by state party conventions, not primaries. As such, the field was divided among many local favorites.[69] Coolidge was one such candidate, and while he placed as high as sixth in the voting, the powerful party bosses never considered him a serious candidate. After ten ballots, the delegates settled on Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio as their nominee for President.[70] When the time came to select a Vice Presidential nominee, the party bosses had also made a decision on who they would nominate: Senator Irvine Lenroot of Wisconsin.[71] A delegate from Oregon, Wallace McCamant, having read Have Faith in Massachusetts, proposed Coolidge for Vice President instead.[71] The suggestion caught on quickly, and Coolidge found himself unexpectedly nominated.[72] The Democrats nominated another Ohioan,

James

M. Cox, for President and the Assistant Secretary of the Navy,

Franklin D. Roosevelt, for Vice President. The question of the United

States joining the

League of Nations was a major issue in the campaign, as was the unfinished

legacy of

Progressivism.[73]

Harding ran a "front-porch" campaign from his home in

Marion, Ohio, but Coolidge took to the campaign trail in the

Upper South, New York, and New England.[74]

On November 2, 1920, Harding and Coolidge were victorious in a landslide,

winning every state outside the South.[75]

They also won in

Tennessee,

the first time a Republican ticket had won a Southern state since

Start your search on Calvin Coolidge.

The Congressional Evolution of the United States Henry Middleton

Unauthorized Site: This site and its contents are not affiliated, connected, associated with or authorized by the individual, family, friends, or trademarked entities utilizing any part or the subject's entire name. Any official or affiliated sites that are related to this subject will be hyper linked below upon submission and Evisum, Inc. review. Research LinksCopyright©

2000 by Evisum Inc.TM. All rights

reserved.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | |||